In the first two parts of this series, we defined resilience as design empathy and detailed the blueprint for durable equipment. This final part elevates the discussion from the product to the system, highlighting the strategic shifts necessary for sustained health system success.

Lessons from Devices That Survive

The most effective MedTech innovations in Africa today are those that have completely redefined their operating parameters. They offer powerful proof that designing for resource constraints drives genuine innovation:

- Solar-Powered Vaccine Refrigerators: These critical devices thrive entirely off-grid. They maintain vaccine integrity across vast arid regions because they were engineered to bypass the power grid challenge entirely. They are a monument to system resilience.

- Uterine Balloon Tamponade (UBT): A life-saving frugal innovation for postpartum hemorrhage. The device is built with cost-effective, readily available materials, often locally manufactured, providing a low-cost, high-impact alternative to expensive imported options.

- Portable Diagnostic Tools: Handheld ECGs and ultrasound devices are flourishing in mobile outreach units. Their small size, robust casing, and battery-powered operation mean they adapt to rough handling and limited maintenance, putting essential capability right where it’s needed.

Engineering for Systemic Resilience

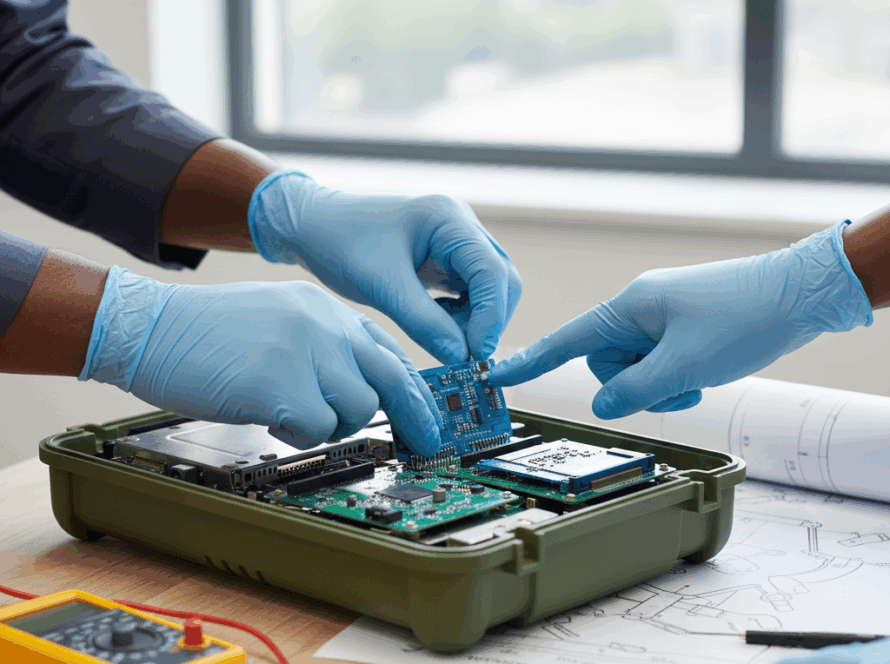

The approach to technology goes beyond simply purchasing rugged equipment; it requires integrating a resilience-first design and validation process into every phase of technology planning and implementation:

- Site-Aware Selection: Every device recommendation begins not with a product brochure, but with a rigorous environmental and workflow audit of the target facility. This determines the actual available power, ambient temperature, and technical skill level before selecting the device.

- Adaptation, Not Imitation: This advocates for localization of designs for African operating conditions instead of importing assumptions from Europe or Asia. This often involves working with local manufacturers to modify hardware for better sealing against dust or to adjust power inputs.

- Empowered Maintenance: This requires investing in building the capacity of local Biomedical Equipment Technicians (BMETs) through certified training programs and, crucially, in creating local or intra-continental spare-part supply networks. Maintenance should be a local process, not an international dependency.

- System Thinking (The Story of Sustainability): A device is viewed not as a standalone product but as part of a functioning ecosystem—comprising power, people, parts, and process. This holistic view shows the value of local expertise. For example, a Biomedical Engineer trained in Kenya or Ghana is positioned to see an oxygen concentrator not as a black box, but as a system component. By combining this local training with devices designed with simplified components and a fortified local supply chain, they gain the capacity to repair it quickly using accessible parts, ensuring the system continues to function. The ultimate focus is on buttressing this entire local ecosystem.

The Future of African MedTech Design

The next generation of African medical devices will not be copies of Western technology. They will be born from African conditions, shaped by the ingenuity of local engineers, and sustained by resilient ecosystems. These innovations will be simpler to operate, easier to repair, and less demanding fragile supply chains—and they will be even more valuable for it.

Designing for resilience is not a compromise on quality; it is the highest form of innovation. It demands a deeper understanding of the user and the environment, leading to devices that not only save lives but sustain health systems.